“America, Again” is a year-long project by the photographers of VII, an exploration of some of the most important issues facing American voters as they head to the polls on November 3rd. This is Chapter 7: American Hope, American Fears, which includes an essay by Alexis Okeowo as well as photo stories by VII members Ed Kashi, Christopher Morris, Maggie Steber, and Danny Wilcox Frazier, VII Mentor Program photographers Nolan Ryan Trowe and Christopher Lee, and guest photographer André Chung. We welcomed Dudley M. Brooks as photo editor for this final chapter.

Essay by Alexis Okeowo

The purgatory Americans have found themselves in this year has been unrelenting, a limbo that burns and chills. First came a global pandemic and lockdown, then an economic recession and a racial uprising, all amid a political horror show. The spread of COVID-19 took the United States by surprise, but the ways in which it devastated American lives in its wake shouldn’t have. The pandemic bankrupted uninsured or under-insured families whose members became sick or died, pushed people onto the street when they lost their jobs and could no longer afford to pay their rent and bills, and left children and their parents hungry. Its ongoing aftermath was destined in a country where the inequities were never truly in the background. The surge of homeless people on the streets of Los Angeles, tent cities sprouting in parks and in front of high-rise buildings, has long been a steady phenomenon. In the Black Belt, the rural poor got sick with COVID-19 and died more frequently than their friends and family in the cities, but were already facing high rates of diabetes and other chronic illnesses as hospitals closed around them.

In New York, for months the center of the American pandemic, I and millions of other privileged residents quarantined in our apartments, terrified and anxious, the silence of the streets outside interrupted only by ambulance sirens and the engines of delivery trucks and buses. For millions of other city residents, life went on as before: waking up, taking the subway to work, interacting with bosses and customers, hoping for kind treatment and fair pay — but all under a cloud of ever-increasing precarity, the threat of sickness, the promise of nothing. The lockdown further revealed the unfairness of belonging to what we would soon call the “essential worker” class, utterly needed and unprotected.

The limbo continues: the confirmation of a new conservative Supreme Court justice weeks after the death of a much-admired progressive one, an uncertain presidential election that will determine the American landscape for decades to come, and future legal battles over the rights of our most vulnerable muddy the horizon. Yet, at the same time, a profound racial reckoning has finally begun. So has a deeper consideration of what kind of country we want, and deserve; beyond suppressive bureaucracy, hours-long early voting lines show that reflection, too.

These photos do many things. They document life across the country during the pandemic, memorialize the protests and federal militarized crackdown in Portland, capture moments in the days of politically mobilized Americans and immigrant Americans and joyous Americans and suffering Americans. Americans still living during what many of us can recall as the most tumultuous period in our lifetimes. The images are riotous and beautiful, startling and haunting, evocative tributes to the work and pleasure of surviving in the most free and arrogant country in the world. Pundits like to say our country is “on the brink,” or “at the edge” — of more unrest, of armed conflict, of chaos. But these photos remind us that we are still trying to do our best, still living.

View “America, Again” | Chapter 7: AMERICAN HOPE, AMERICAN FEARS here.

Shopping along Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, Calif., on July 19, 2020.

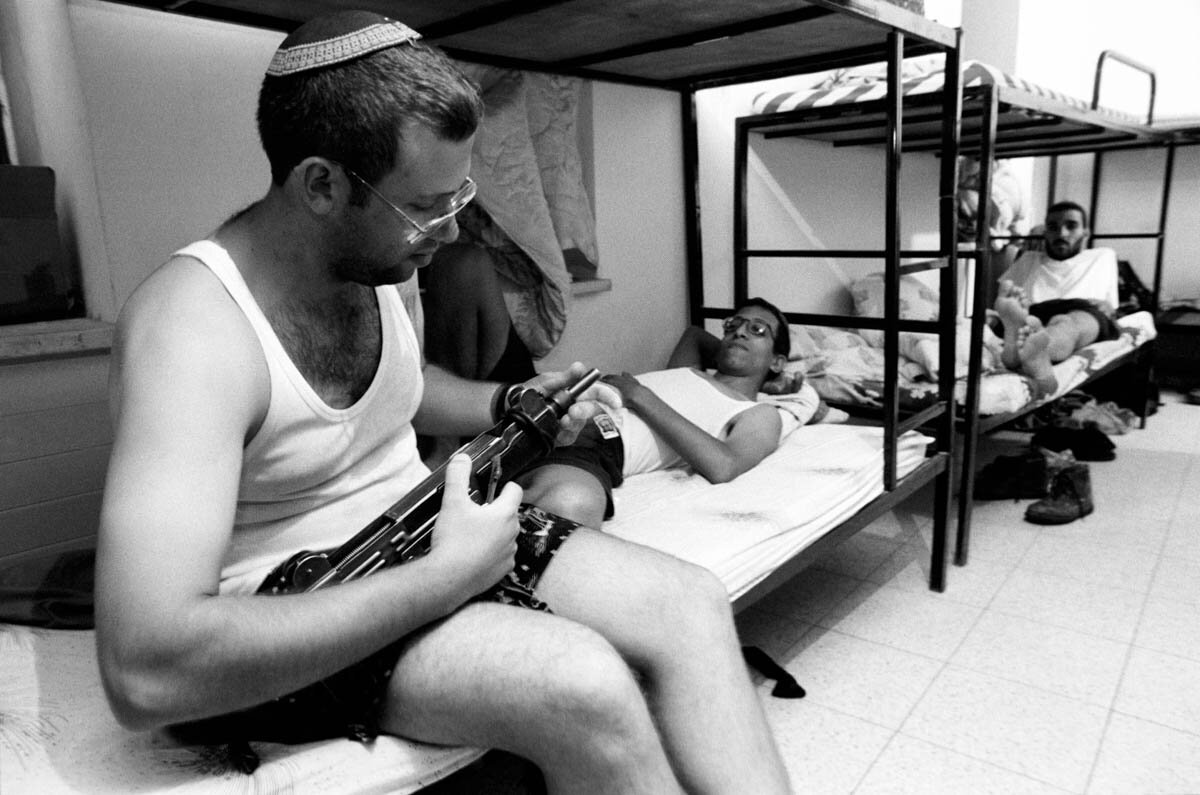

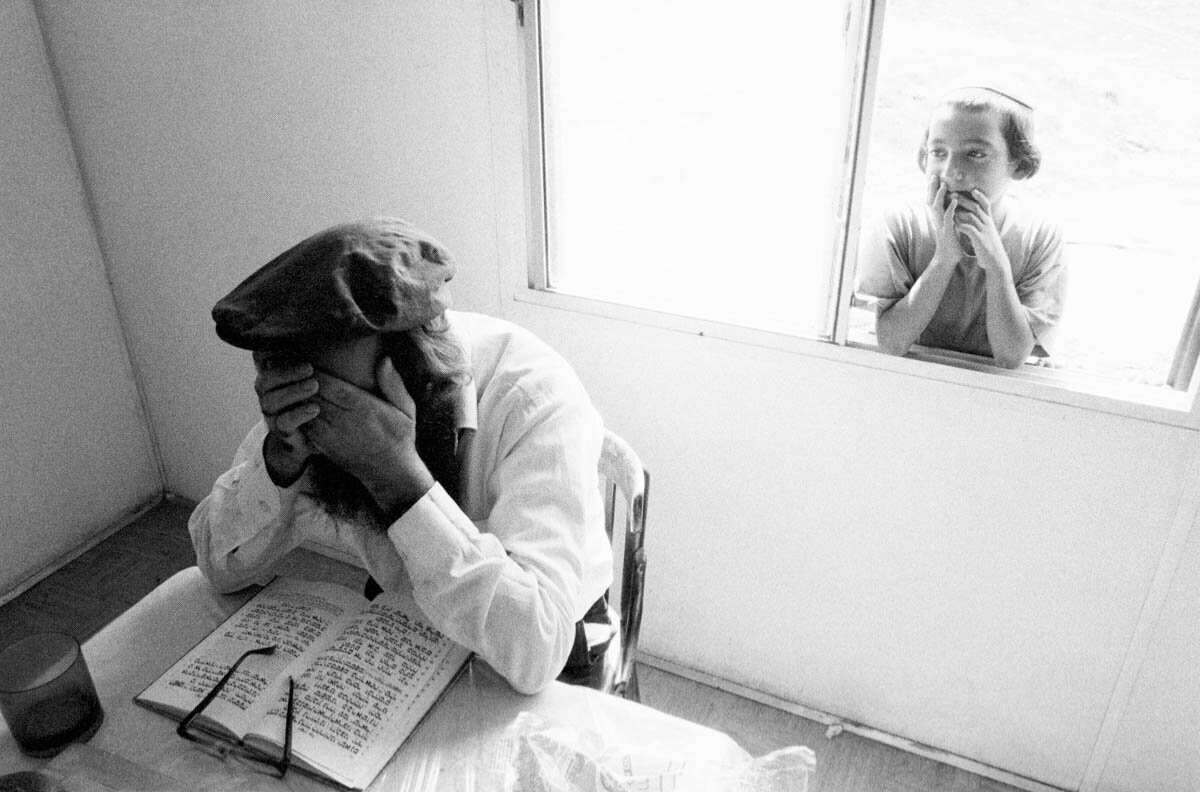

The Divided State of America

Photos and essay by Ed Kashi

This summer I had the privilege to work with Jyllands-Posten, one of Denmark’s major daily newspapers, on a 30-day road trip from Los Angeles to New Orleans. The mission was to work on a series of stories about the state of America, as our nation approaches the 2020 election. In this particular moment, the United States can more accurately be known as the divided states.

This is Trump’s America, not mine. As with my work, I try to keep an open mind and heart, and through decades of working across all 50 states and over 100 countries, I’ve learned that America is a magnificent composite of diversity and quirkiness, a massive spectrum of both wealth and health; but at its core, there is a rot. The rot of racism and genocide. The cancer that was embedded in our founding has never entirely been eradicated. While we have made tremendous progress and continue to do so, we are still hurting and bleeding from our endemic racial injustice. With the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, after far too many other unnecessary deaths of Black people at the hands of police officers, this rot has been exposed for a new generation that has taken up the call to make change.

What I documented during this journey is a country and people divided in the midst of an evolving spirit of protest. This set of images does not claim to capture the microcosm of America in 2020, but the breadth of stories and images represents a country at a crossroads, grappling with a severe wealth gap, continued racial injustice and a body politic that for some are itching for civil conflict to justify their positions. I continue to ask myself, a child of the revolutionary America of the 1960s and 70s, how have we gotten here.

We Keep Us Safe

Photos and essay by André Chung

At the beginning of the summer of 2020, as hundreds of thousands took to the streets to protest police brutality, I did so as well. This wasn’t the first time I witnessed protests against the barbarity of the state, but as we’ve seen, this time was different. As the movement coalesced, protesters in my hometown of Washington, D.C. have been out in force every single night. When news cameras leave, the cops move in with pepper spray, gas, and munitions. They arrest people en masse to clear the streets, only to release them the following day with “no paper,” the term they use when there are no charges to file. They continue to kill Black men. All over the country, every week, there’s another Black life lost at the hands of police and another community demands an end to the wickedness. In D.C., two more young men have died during police encounters since protests began. Deon Kay. Karon Hylton.

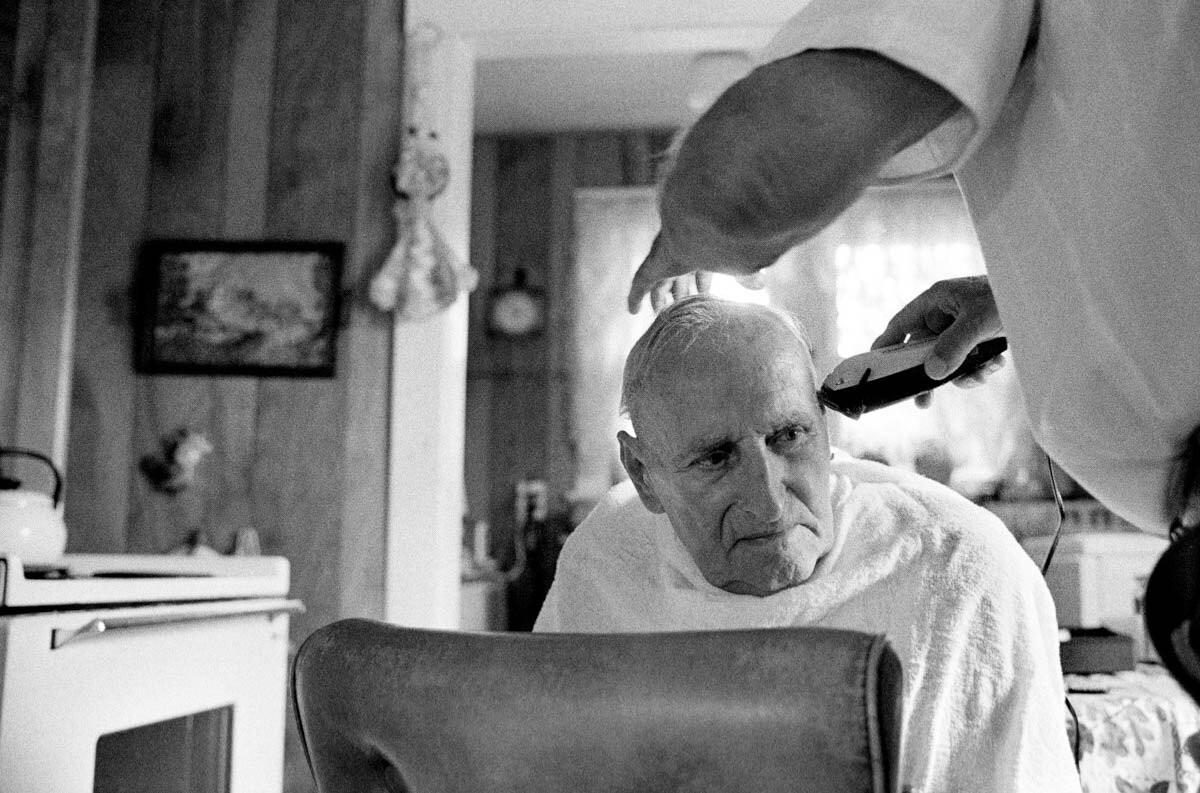

As the police have historically resisted reform, there have been calls for police to be defunded and even abolished. Protesters believe that police, entrusted to protect and serve, do neither, and ask, “Who keeps us safe?” The response, “We keep us safe!” They protect and defend each other, not just from police but from opposition activists, the media, and anyone who would do harm. A man on an electric scooter, who disrespected some of the Black women at a march, was run off the plaza by protesters but brandished a knife and menaced himself and the crowd. A protester disarmed him while Metropolitan Police stood by, only to tase him after the man was subdued. At Black Lives Matter Plaza, the focal point in D.C., protesters set up food tents, medic stations, and give each other haircuts. At a tent city occupation of the Department of Education, protesters watched the presidential debate on an inflatable screen and settled into games of chess and spades to pass the night. The dedicated group of several dozen activists has been hardened by the protests but have become close. The movement is not only about rage, it is about love as well. It is about love for Black lives and the love and respect for those who would acknowledge that Black lives matter. They determine the community here, and it defines a generation.

Sharece Crawford, At-Large Committeewoman, addresses activists and community members outside 7th District headquarters. Residents and activists react to the police slaying of Deon Kay, 18, who was shot by MPD officers who say that Kay was armed and had a weapon at the time of the shooting. Body cam footage corroborates the officers’ version of events, but family and community leaders and activists demand to know why non-lethal methods were not used. Activists rallied at 7th District headquarters where they were met by a phalanx of officers who stood sentry at the entrance to the precinct.

Making a New Life on Dreams and Fears in Little Haiti

Photos and essay by Maggie Steber

Little Haiti is a place about memory as much as anything. Even if their memories are fearful, as is the case for many Haitians, they are still memories of the homeland which they have tried to re-create in Miami, Florida. Every story here is a story of survival, about escaping violence, about winding one’s way through an impossible stacked-decks immigration system, and about keeping some vestige of culture, language, history, and dreams alive. If there were ever a prime example of the racism toward and hardship of being an immigrant in America, it can be found here in Little Haiti.

As with all cultures, the beating heart of Haiti is found in its history, which is singular. Enslaved Africans overthrew their French masters to achieve the only successful slave revolt in the world at a time when the world’s economies rotated on the backs of enslaved people. They beat back Napoleon’s armies and still had to pay reparation to France for taking over the richest colony in the French crown. Led by revered heroes, Haitians built a new nation, full of sophistication and intellectual abilities. But the world turned its back on Haiti and isolated it to keep news of a slave revolt secret. It retained its African heritage but also embraced a rich culture of art and letters.

The main street of Little Haiti is pretty with gingerbread features on colorfully painted stores and a large marketplace. Currently, it is holding off the invasion of gentrification. Important Haitian leaders and artists live here. Amid them is Jean Mapou whose bookstore sells thousands of books in Creole, French, and English and is a center of culture. He is considered to be a Poteau Mitan (elder statesman). Next door, internationally-known artist Edouard Duval-Carrié creates bodies of work that draw from the traditions of vodou and Haitian history, and down the block renowned writer Edwidge Danticat lives with her family writing books that break the heart and lift the spirit.

Isolated from much of Miami by culture and language, Haitians turn to local community leaders for social services and assistance. Two names known to all are Gepsie Metullus and Marleine Bastien. Gepsie is executive director of SANT LA Neighborhood Center where Haitians can go for help with unemployment payments, medical help, social security, and taxes. Marleine Bastien, a venerable political leader, is the executive director of FANM, the Haitian women’s agency, which provides women with help finding employment, domestic violence, after-school child-care services, and an annual health fair. Bastien also leads demonstrations against U.S. immigration policies and has run for political office.

At the heart of the community is Notre Dame d’Haiti Catholic Church, overseen by Father Reginald Jean Mary. The church is a community center and hosts a school for children and adult Haitians who learn to write Creole and English, even in their later years. Haitian teens have access to computers and etiquette classes and seniors have morning exercise classes.

Over in the community garden, Prevenir Julien makes a living thanks to the non-profit that sponsors him. He and his son Belix, 12, have a nice one-bedroom apartment nearby. They came to the U.S. on a medical visa after Belix was critically wounded during the 2010 earthquake from which the country is still recovering. Belix recovered and is receiving a free education that Prevenir would have had to pay for back in Haiti.

As for street culture, Serges Toussaint paints murals around Little Haiti and takes visitors on tours of Little Haiti’s streets in an effort to grow appreciation for the neighborhood.

No matter what pressures Haitians face in the U.S., they continue to dream about a better and more peaceful life, free from political violence and crippling economics. Whatever their fears, they have learned to face them full on. It is still not an easy life, but they get up every day and do it all over again, in search of that elusive American dream that promises so much but often falls short for these immigrants.

These photos show how Haitians help each other to settle into a new land vastly different from their own in an area called Little Haiti in Miami, Florida, a vibrant immigrant community that struggles to recreate a part of their old country in a new land by maintaining cultural aspects of their lives and with the help of organizations in Miami, mostly run by members of the Haitian diaspora. Haitians come with dreams but live with fears of racism and discrimination and often temporary status that is constantly challenged by changing immigration rules.

A Haitian nun prays during mass at Notre Dame d’Haiti, the Catholic heart of Little Haiti. Mass is held in Creole and offers a safe and caring place in the community. The Catholic church, which raised money to build a new church, also provides school courses for young students and for Haitians who want to learn to speak and write English, as well as fitness classes for older Haitians.

Unlearning

Photos and essay by Nolan Ryan Trowe

Some people see me as a disabled photographer instead of a photographer. It’s true that many of my stories have focused on disability, as I am a person who happens to have a disability. However, when people choose to only see my work through the lens of disability, they miss out on a lot. On the surface it’s a disability, but underneath that, when people look beyond my wheelchair and leg braces and frailness, they would see that the work is about ideas that every human can relate to: fear, shame, masculinity, intimacy, anger, love, and family are just to name a few. And even more so it’s about learning to love myself so that I can properly love others.

Until I became disabled, I never had to worry about being put into a box based off of a physical immutable trait — you know, I had that privilege for nearly 23 years, and I’ve lost it for the last four and change; it’s shifted the way I navigate the world physically and mentally. It makes me question everything, because one day the world treated me one way, and overnight it treated me another. I never realized how much pain I was in, how much harm I had done to myself.

My personal journey, much like my country’s, is to unlearn most of what I was told about myself.

This project was produced with support from the Magnum Foundation.

The author stands for a self-portrait in his home in July 2020. His genitals and thighs are obscured.

America

Photos and essay by Christopher Morris

I’m struggling with what to write here, with the new reality of the country of my birth. I first was assigned early in the pandemic to go to the small Georgia town of Albany, where I spent several days with the County Coroner as he struggled with the surging deaths in his community, with this unknown new disease that was flourishing in his county. Racing through city streets with his sirens blaring and lights flashing, when we passed vehicles, the occupants would stare in pure horror, as if the Grim Reaper himself had just passed them by.

After this experience, the virus for me and my family became something serious that we needed to understand and to pay very close attention to. I’ve spent the past eight months now protecting myself and my family. I believe in science and could understand that simply wearing a mask whenever I go out into public was my best defense and protection for others with this new world we all live in. That brings me to today, after attending an extremely large Trump campaign rally here in Florida where I live. I’ve covered over 20 conflicts up close over my 30-plus-year career, and I have never been more shocked and more afraid at what I witnessed at this rally. Thousands of American Trump supporters crammed into an open field next to a stadium with over 70% of participants maskless, shoulder to shoulder. Blindly worshiping their dear leader, on cue screaming “lock them up,” and laughing and jeering at the mention of lockdowns and mask-wearing. It was extremely frightening, and I do not scare easily. But what I witnessed at this rally was a true “cult of death.” I fear for my country and what the months will bring.

Albany, Ga., where an increase of COVID-19 deaths surged in this rural, mainly African-American community. April 5, 2020.

To Peacefully Protest in Portland

Photos and essay by Christopher Lee

In the early weeks of July, federal law enforcement from agencies such as Border Patrol, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Department of Homeland Security were dispatched to Portland, Oregon, in the wake of the ongoing protests for civil rights shortly after the death of George Floyd. This was part of a mission called Operation Diligent Valor by the Trump administration. There, agents armed with less lethal munitions met peaceful protesters every night to “take care” of the activists that would congregate in front of the Mark Hatfield Federal Courthouse, according to the president. While the protests have been largely calm and nonviolent, federal agents would dramatically escalate violence during the demonstrations, discovered in an analysis by The New York Times.

In a letter written by Portland City Council Commissioner Chloe Eudaly, condemnation of the presence of federal law enforcement was outlined. There, Eudaly stated that Portland was a “test run,” saying “the Department of Homeland Security has openly stated that they intend to replicate these tactics in cities across the nation.” While we might not know what the November election will bring, one thing is for sure: the fight for civil rights in America will continue on no matter who sits in the Oval Office. My fears remain for the future of our rights as Americans to fight for what we believe in. Will this be a lesson that we will learn for how we as a country interact with demonstrations in the streets, or will Portland truly become a preview for what's to come?

Pro-BLM protesters and members of the Wall of Moms are seen near the Hatfield Federal Courthouse in Portland, Ore., on July 25, 2020.

Cowboy John

Photos and essay by Danny Wilcox Frazier

I drove up to the Neumann Ranch after getting lost while on my way to Cactus Flat (population 12 in 2008). I drove past a Minuteman Ballistic Missile historic site and ended up on what Julie Long, John Neumann’s girlfriend, described as a “broke down horse and cattle ranch.” John and Julie took me in, years later joking over dinner that if they knew I meant it when I asked to move in, well maybe the answer would have been different. This photograph, the most well-known from my work on the Great Plains, is something John was proud of. It was recognition that his life, with all the rusty edges, broken bumpers, and pain was also beautiful. It wasn’t all polished up like a big city, but as he once told me, “We might be poor, but we still have fun.”

John took his life on June 9th, 2019. He left behind a 6-month-old son, Stetson, and longtime girlfriend, Tabatha Swartz, as well as many loved ones and friends. Tabatha continues to raise their son on the Neumann Ranch, fighting to maintain the operation for when Stetson takes over, John’s dream for his son.

Suicide is personal for me, a part of my life since I was a teenager. While trying to understand John’s death is a heartbreaking daily reality for Tabatha and all those who love John, there is a piece of this that must be spoken. John suffered from ankylosing spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy joints. “John was always hurting because of his joints,” says Tabatha. John and Tabatha tried to get John to specialists that could help, but the waitlist was a year long at the (one) doctor in their region. John was spending $600 a month for insurance so he could receive medical care that was then 12 months out of reach. “It was very physically painful for John and he had tried different ways to control the pain, but we weren’t rich. John was just waiting, just waiting all the time and he was tired of it,” Tabatha says. “There was no access to the care John needed. Maybe down the road (there would have been), but John didn’t wait long enough.”

Rural America is seeing a dramatic rise in suicides. Studies show the rate of suicide in rural counties is 25 percent higher than major metropolitan areas. Since 2000, the overall rate in the United States saw a 41 percent rise in suicide among people ages 25 to 64. Factors pushing the increase in rural communities include poverty, low income and underemployment, isolation, neglect, lack of access to mental healthcare, and the stigma mental health treatment has in rural culture.

In the remote communities surrounding the badlands of South Dakota which includes the Neumann Ranch, access to healthcare and the money to pay for it are real barriers. The system failed John. “It was all about pain for the most part, physical and mental,” says Tabatha. “John’s body hurt so much he didn’t want to be here.” Maybe if the care John needed was readily available, his pain could have been managed. Maybe if our society valued access to healthcare for all, no matter wealth, race, or location, suicides like John’s would fall in number. Until we work together to find solutions for those outside of the ultra-wealthy ranks, the impact of wealth consolidation will continue to take loved ones, like John, from us all.

John Neumann, Cactus Flat, South Dakota, 2008.

Contributors

Essay by ALEXIS OKEOWO, writer of A MOONLESS, STARLESS SKY: Ordinary Women and Men Fighting Extremism in Africa, which won the 2018 PEN Open Book Award, and a staff writer at The New Yorker and a contributing editor at Vogue.

Photo editing by DUDLEY M. BROOKS, the Deputy Director of Photography for The Washington Post, where he manages the creative strategy and production of photo-oriented content for the Features and Sports sections. He is also the Photo Editor for The Washington Post Magazine. Preceding this, Brooks was the Director of Photography and Senior Photo Editor for the monthly magazine Ebony and its weekly sister periodical Jet — both formerly published by Johnson Publishing Company in Chicago.

Guest photography by ANDRÉ CHUNG, an award-winning photojournalist and portrait photographer based in the Washington, D.C./Baltimore area.

About “America, Again”

Exactly one year before voters go to the polls on November 3, 2020 — and three months before Iowans gather for their caucuses — VII launched the first chapter of our year-long collective election coverage, “America, Again.”

This project emerged among a few of the VII photographers with the intention of focusing attention on the issues that will dominate the U.S. election. The VII Foundation and VII Academy have stepped in to support the project in recognition of the importance of critical and independent storytelling in civic discourse. We will produce stories on material issues that people worldwide are wrangling with, not only Americans. We’ll cover issues that are used to divide us, and that allow populist politicians to undermine the values that are foundational to our societies.

“AMERICA, AGAIN” | CHAPTER 1: IOWA

“AMERICA, AGAIN” | CHAPTER 2: THE ENVIRONMENT

“AMERICA, AGAIN” | CHAPTER 3: AMERICAN DREAMS

“AMERICA, AGAIN” | CHAPTER 4: INTERRUPTED

”AMERICA, AGAIN” | CHAPTER 5: AMERICAN MYTHS

”AMERICA, AGAIN” | CHAPTER 6: AMERICAN IMPERIUM

”AMERICA, AGAIN” | CHAPTER 7: AMERICAN HOPE, AMERICAN FEARS